“I Can See My Family In Her”

News of Note

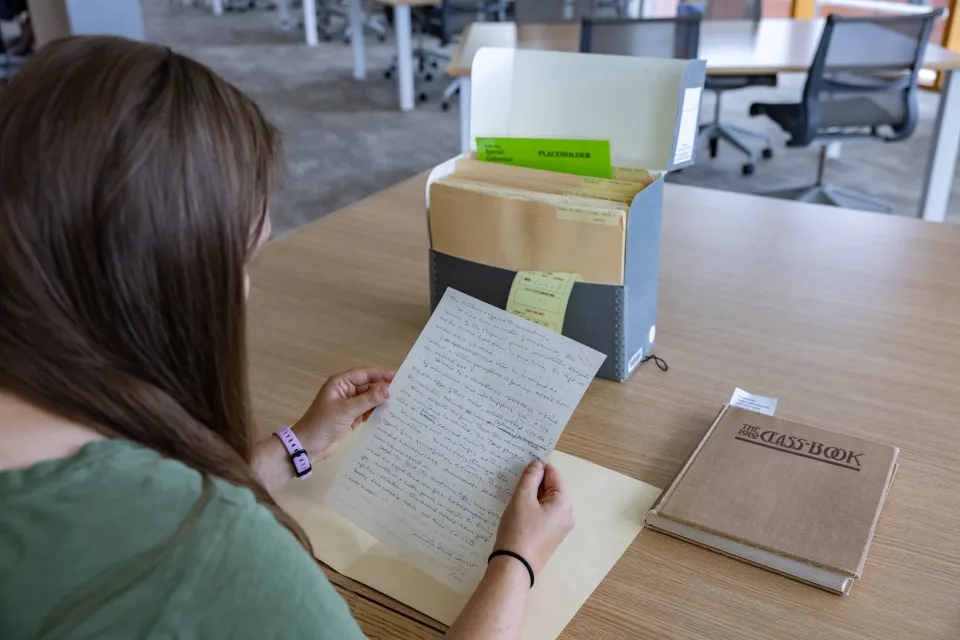

A chance moment in Special Collections sets one Smithie on a journey into the past—and future

Photo by Jessica Scranton

Published October 7, 2024

Kady Wilson saw her great-grandmother for the first time in the Smith College Special Collections.

Wilson was a high school junior and was touring Smith with her mom. They both knew that several relatives had attended the school: An aunt in 1978, a grandmother in 1939, and a great-grandmother in 1912. With those Smith connections in mind, her mother suggested the two visit the archives.

They were hoping to find a bit of information in old yearbooks. What they found—and what Wilson would rediscover decades later—was a great deal more.

Photos by Jessica Scranton

For Wilson, that visit had been a pivotal moment. Not only did she enroll, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 2015, but she returned again for another Smith degree—this time to earn a Master of Science in 2021.

In August, Wilson was named the new Manager of Living Collections for The Botanic Garden of Smith College. Wilson’s new role, which Elaine Chittenden retired from in March, will include carefully managing records on each individual plant in the Smith collection—some dating back to her great-grandmother’s era.

During her first month as a staff member, Wilson headed to Special Collections to explore the archives once again, to see photos of her grandmother and great-grandmother for only the second time, and to talk about how for her, lineage, family lore, and Smith could all intertwine.

Wilson’s recent visit begins when Head of Special Collections Public Services Leslie Fields brings out a slim gray box of folders and demonstrates how to carefully remove a file and mark the space where it belongs.

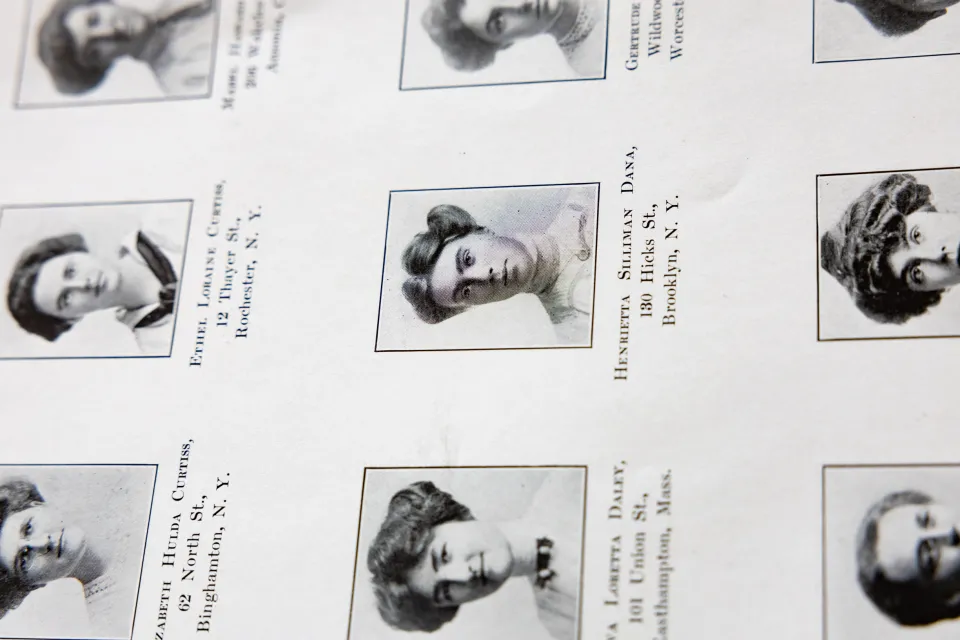

Wilson slips a folder out and opens it carefully to reveal two photos and a handwritten letter. She turns the photos over with care. One, taken in 1909, features a young first-year Smith student wearing a wide black hat and smiling slightly. It’s Wilson’s great-grandmother, Henrietta Silliman Dana Hewitt.

“Before I saw these, I had never seen a picture of her before,” Wilson says. “So I’m sure that influenced my decision to come to Smith.”

Wilson’s family—which has the distinction of being able to trace both sides to the Mayflower and has included notable members such as the first governor of Connecticut—has long treated genealogy as part hobby, part mission. (Her parents met because their parents were both genealogists.) This knowledge of family history runs so deep that Wilson can easily list off names and anecdotes of predecessors multiple generations back: There’s the great-grandmother who hated her name as a child, so she approached her namesake to ask that they both switch from “Henrietta” to “Pansy.” She would later paint watercolors of Smith plants and stand on top of Hatfield House to watch the famous Halley’s Comet pass by.

“She was one of the few students who still did their homework that night,” says Wilson. “She was that sort of person.”

There was the grandmother who, as a Smith student, was working with other staff on the college newspaper when the 1938 hurricane blew their pages all over the room; the group watched in disbelief as towering trees on campus came crashing down in the wind.

There was the aunt whose work-study in Lyman involved deadheading camellias. The still-lush blooms she would pick and sell, on behalf of the college, to corsage shops along Green Street.

“It was a very normal dinner conversation to just be like, ‘Oh yes, your fifth great-grandfather …’” says Wilson. “We talked about these people all the time, but we didn’t have photographs of them.”

Knowing a family history this deeply and well is a type of privilege of which Wilson is acutely aware. She also recognizes that family historians have likely glossed over many negative moments in their accounts. Even as they remember and repeat the stories of the past, she says her family is also “choosing what history to tell.”

Still, Wilson is in the unique position of having a more extensive knowledge of her predecessors than most. Paging through an old yearbook, Wilson recalls that as a student in the 1900s then-Henrietta Silliman Dana majored in botany and German and was extensively involved in college life. At various points, Dana was a member of the cricket team, the German club, Phi Beta Kappa, the Alpha Society, and was president of the biological society. Talented at sewing, Dana also created sets for Smith plays.

Looking at Dana’s photo now, Wilson says, “I can see the women in my family in her, definitely.” She pauses, struck by the impact of what previous generations leave behind. The items in the archive’s folder are precious and few: A picture of her great-grandmother, a picture of her grandmother. If the photo and document had been in her family’s care, would they still have survived, she wonders.

“Sorry, it’s got me a little emotional,” Wilson says, wiping her eyes. “I really like records, which is why I’m in charge of the records at the botanic garden. I’m glad there are records of these things.”

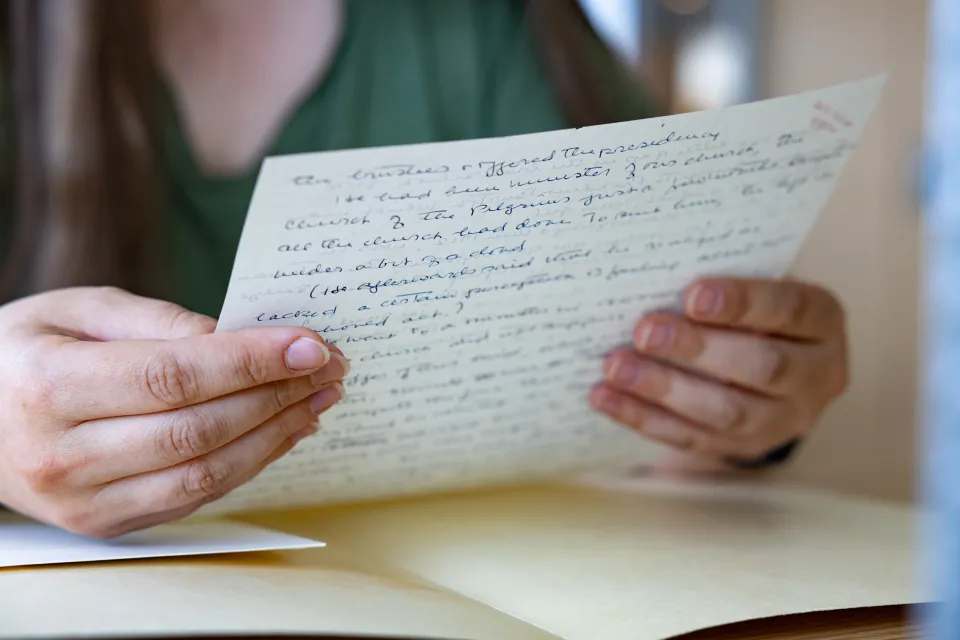

Wilson sets the photos down and turns to a letter written in her great-grandmother’s neat cursive. As Wilson scans the text, she realizes that she is reading an insider's take on a notable moment in Smith history. In her first year at the college, Dana had been called upon to give a campus tour to Marion LeRoy Burton. Burton, then a reverend in Brooklyn, was in the final stages of being considered for a prominent position at Smith; He would go on to lead the college as Smith’s second president, from 1910 to 1917.

In the archives, over a hundred years later, Wilson begins to read aloud.

“[I] was in the studio of the Hillyer Art Gallery when the custodian came upstairs, breathlessly, saying ‘President Seelye is downstairs and waits to see you.‘ I rushed down. There he was. He said, ‘I understand that you are the only parishioner of Mr. Burton in the college. He’s coming here as speaker for Sunday for all colleges [sic] tomorrow. He arrives this afternoon and will be met and taken to Chapin House. Unfortunately, I have a faculty meeting this afternoon. Can you come for him and show him the college?‘”

Dana agreed. “Dr. Burton certainly saw it from a freshman’s point of view,” she would later note.

To show her prominent visitor around properly, Dana requested the keys to two locations at Smith. Even as a first-year, she knew these two places were the most “outstanding features of the college.” The minitour started with Smith’s notable art gallery.

What other location did Dana want to show off? A century before her future great-grandchild would accept a position there, Dana took her visitor to what she considered Smith’s best place: Lyman Plant House in the botanic garden.