We Wear Shoes, We Use Sunscreen, We Carry Narcan

Campus Life

Anonymous and peer-led, a harm reduction effort on campus aims to help those who need it most

Photo by Liliana Hetherman ‘25

Published May 14, 2024

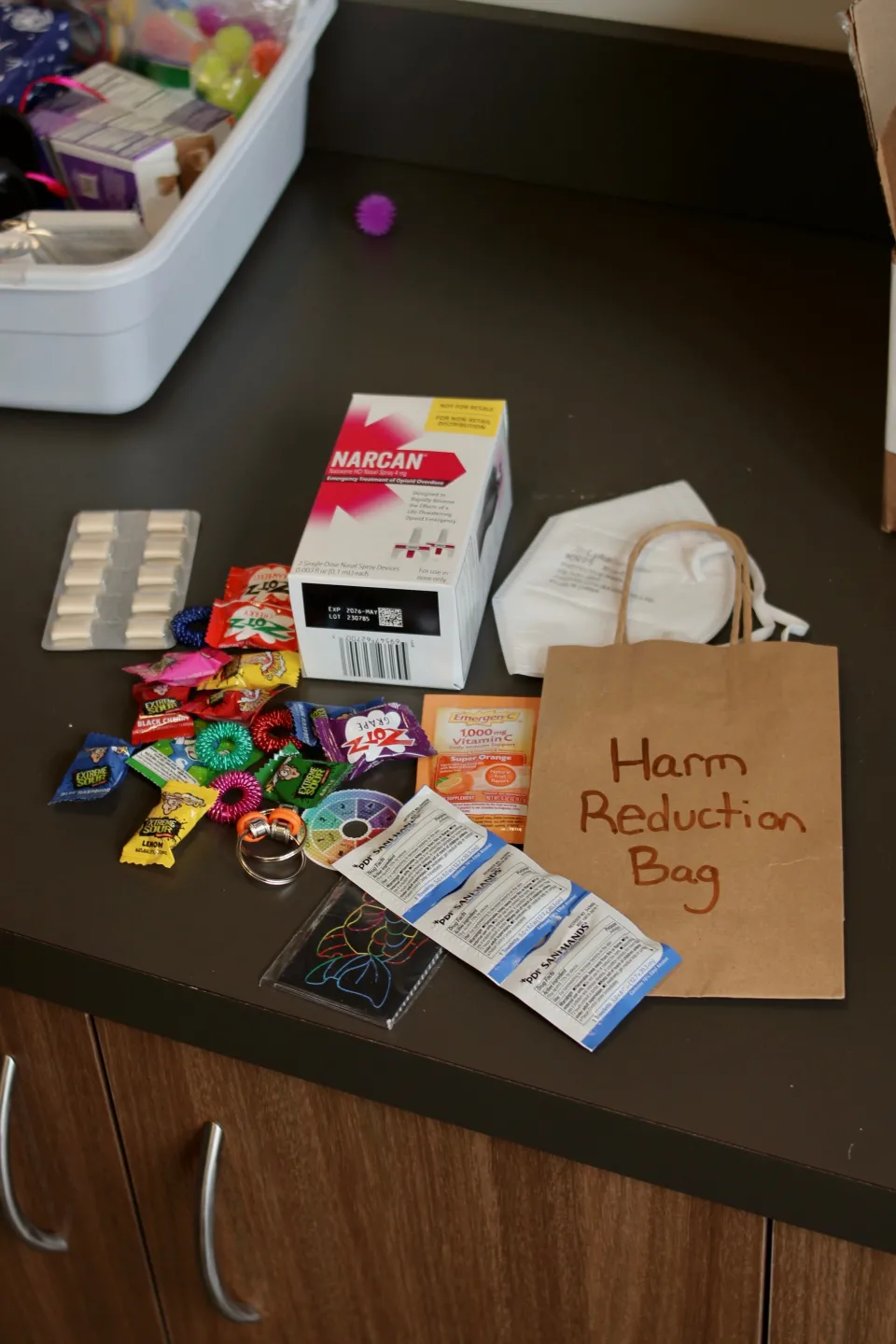

Cailin Young ‘24 quickly moves around the interns’ work room in the Schacht Center, gathering supplies. She grabs handfuls of condoms and lube, masks and nicotine gum, test strips and doses of Narcan, and small instruction pamphlets in English and Spanish. She pokes through piles of colorful rubber bands and fidget toys, adds a few sour candies.

“Our next bag is a nicotine cessation and a self-harm and the COVID,” she says, pulling out a bag and filling it with items, all aimed at unique forms of harm reduction. “Everyone’s a little bit different.”

Then she clicks through a spreadsheet on the interns’ shared desktop and begins again.

The humble business of filling small brown paper bags, marked with unique codes and arranged on a countertop, is part of a revolutionary effort by student Community Health Organizers (CHOs), and spearheaded by Young, to support students on campus who need it the most: Students dealing with addictions; students who need supplies for safe sex but can’t afford them; those who are struggling with thoughts of self-harm.

The effort, which launched in the fall and has evolved over the past year, has proven incredibly successful, with roughly 300 requests for the service since it began. All aspects are student-run, by design, to help mitigate any fears of those requesting the services.

“It really does just come back to the basic principle of trying to support people in living their best lives,” says Young. “No matter what that looks like.”

Photo by Liliana Hetherman ‘25

Addressing needs in a preventive way—so that help for addiction is as routine and free of stigma as wearing a car seatbelt, for example—was programmed into Young at an early age. Warm and friendly, with armfuls of bangles, Young has the ability to seamlessly recall a wide range of opioid addiction statistics, such as how rates of opioid-related deaths in New England are more than two times the national average. She credits her parents, especially her mother, a nurse, with teaching her about the “public duty to the world to be a good person and to care for people.”

As Young started high school, she recalls, her mother supplied her with doses of Naloxone and training on how to use them. Young began routinely carrying the emergency nasal spray in her bags, switching them between backpack and purse along with her lipgloss and keys. It was not until college, though, and a visit to an off-campus residence, that she administered a dose.

“It was a situation where I didn’t expect it,” says Young. “I was at a friend’s house and one of her roommates ended up overdosing unexpectedly. None of us knew that he was using in that moment.”

The roommate recovered, but the moment drove home to Young how important immediate access to Naloxone could be when it came to an emergency situation.

It was against this background that Young, a psychology major and Russian studies minor with a concentration in community engagement, joined the Schacht as a CHO. She began working with her peers on two parallel efforts: Installing NaloxBox stations across campus (which was successfully completed over the spring with six campus boxes and training for over 500 students) and creating a program where students could make anonymous requests for help.

For Young, creating new avenues for harm reduction was an obvious opportunity—a chance to mitigate risk in the lives of other students. “Everyone uses harm reduction,” she says. “We wear shoes, we get vaccinated, we wear seatbelts, we use sunscreen… Those are a set of principles that you can apply to anything, which is reflected in our bags.”

Photo by Liliana Hetherman ‘25

The bag program started in the fall with four offerings, all designed around community needs and evidence-based practices: A nicotine harm reduction kit (nicotine gum, QR codes to resources on quitting or modifying nicotine intake); opioid harm prevention kit (fentanyl test strips, two doses of Narcan with information on how to use it, and an online video training requirement); a safer sex bag (condoms, dental dams, gloves, and an informational sheet); and a self-harm reduction bag (sour, hot, or popping candies, a wide range of fidget toys, temporary tattoos, journals, and scratch art pads).

Based on community feedback—including a request by housekeepers, who were worried about encountering items like razors or tattoo needles in the trash—the offerings expanded to include a small red sharps disposal container and a COVID harm reduction kit (mask, nasal spray, a test, gloves). Depending on their contents, each bag in the program costs anywhere from $2 to $20 to create.

While most of the funding for the bags comes from Smith’s Wellness Department budget, the Narcan is funded through a grant by the state Department of Health’s Community Naloxone Program (CNP); fentanyl test strips are provided for free by the DPH’s Massachusetts Health Promotion Clearinghouse; and the NaloxBoxes were supplied by Hampshire Hope, a Hampshire County coalition focused on drug recovery and harm reduction.

The bags, and their contents, can be mixed and matched as much as needed. Students enter requests through an anonymous Google form, adding a specific, unique code (known only to them) to identify their bags, and Young or one of the other CHOs fulfill the requests. Completed bags are left at a table on the first floor of Schacht, near a quiet stairwell and the center’s lost and found.

That placement is deliberate, notes Young, who added that bags and NaloxBoxes around campus are placed away from cameras or prying eyes. “We do try to be really cognizant,” she says, “because we understand that the students who may be the most cautious or hesitant with engaging with these services are the ones who need them the most.”

Due to the layers of anonymity, tallying the direct impacts of the program can be tricky. Anecdotally, students have told Schacht Center staff that harm reduction bags have helped them stop smoking, or that they distributed fentanyl test strips among friends before heading out to a party. Requested bags are occasionally abandoned on the first floor table, but Young says the majority are picked up.

When it comes to the success of the self-harm effort, Young is quick to credit the contributions of her fellow CHOs and the support of Schacht staff. Who exactly deserves the most kudos for launching the program, in fact, is the subject of a good-natured debate at the Schacht Center, which becomes clear when Sunny Windorski ’20, a health educator and Young’s supervisor, pops into the intern room looking for binder tape and discovers Young working on the bags.

“I think it’s a great idea. Cailin came up with it—” they begin.

“I thought you came up with it!” Young interrupts, and they both laugh.

“At some point it happened,” amends Windorski. “I really wish something like this had existed when I was a student. This offers an option for people who recognize they need help, recognize they want to change—and have the autonomy to change in a way that they want to.”