Women’s Clothes and the Stories They Tell

News of Note

For nearly 50 years, the Historic Clothing Collection has been one of Smith’s hidden gems. Now, it’s finally coming into the light.

Photograph of Kiki Smith ’71 by Shana Surek.

Published May 8, 2024

Part One: The Collection

With the publication of Real Clothes, Real Lives by Kiki Smith ’71, and an exhibit at the New-York Historical Society set for later this year, the Smith College Historic Clothing Collection is finally getting the recognition it deserves. This series will chronicle what makes the collection unique, its pedagogical possibilities, its impact on Smith students and alums, and the laborious process of sharing the collection with the world.

One of the most subversive actions Smith students and alums have undertaken over the past 50 years has been the creation and conservancy of the Smith College Historic Clothing Collection (SCHCC). Until fairly recently, the idea of studying—let alone, collecting—women’s quotidian garments had been a hard sell to some experts. Writing about the collection for The New York Times, fashion director and chief fashion critic Vanessa Friedman noted, “They are the kinds of garments generally overlooked or dismissed by museums and collectors of dress, who tend to focus on fashion as an expression of elitism, artistry, aspiration.” By spotlighting what have been deemed “the social uniforms of the many roles that women have held throughout the years,” the Smith collection provides a unique window into the experiences of women.

What started as a simple effort to protect a few interesting items from the jumble of abandoned stage costumes in the theatre department has evolved into a fascinating archive that chronicles through various fabrics, colors, textiles, textures, and clothing styles the untold stories of women’s everyday lives at work, at home, and at play. Housed in the basement of Smith’s Mendenhall Center for the Performing Arts, the collection has been lovingly expanded, cataloged, curated, and cared for by Kiki Smith ’71, professor of theatre since 1974. “I just knew that some of the pieces that would be destroyed on stage would be much more valuable as a resource—a visual—for research,” she says. “I put a bunch of gray metal cabinets out in the hallway and just kept going through what we had.”

Those gray metal cabinets are still in use today and now contain about 4,000 garments and accessories, some dating from the 1800s. Among these are myriad house dresses, maternity clothes, waitress uniforms, and petticoats in addition to undergarments, period care items, stockings, and aprons—many painstakingly altered, patched, and repaired countless times.

Smith says identifying and getting information about the various garments was slow going at first. “We had no Internet, of course, and certainly nobody was collecting the ordinary stuff, and very few people were writing about it that I knew of,” she says. She persevered, and with the help of Nancy Rexford—former curator of costumes and textiles and director of Historic Northampton, who has written several books on historic clothing—Smith became increasingly adept at reading a garment. She learned how to begin to identify the number and type of alterations, the pattern of faded material, the mended tears, and the types of stains—all intimate details in the story of the life of the woman—or, in some cases, women—who wore the garment.

Cotton work bodice, circa 1860s: Also, called a “sack” or “Josie,” these cotton work bodices were worn by women who engaged in more physical work on a ranch or farm. The lining of the bodice shows a liner likely pieced together from older garments.

“Sometimes classic art, often like classical music, is not terribly accessible to someone that doesn’t know what they’re looking at. But we all wear clothes.”

Beth Pfaltz Welsh ’80 is credited with formalizing the creation of the SCHCC. A longtime sewer, she jumped at the chance to work in the costume department as a student and was instantly taken with the fledgling collection. Welsh had often attended exhibitions at the Met’s Costume Institute, which she loved, and suggested to Smith that they create a museum telling the story of women’s lives through clothing. “Sometimes classic art, often like classical music, is not terribly accessible to someone that doesn’t know what they’re looking at,” Welsh adds. “But we all wear clothes.” Getting the collection off the ground was no easy task, but she was up for it. “I'm 19 with all the bravado of a 19-year-old,” recalls Welsh, “and no reason to think we can’t move mountains.” After attending a workshop in protecting historic clothing led by Rexford and completing an internship under the costume conservator at the Met, Welsh secured a $10,000 grant from the Celanese Corporation, which was known at the time for its synthetic silk-like fabric. Welsh, who these days heads a real estate management company, wrote the collection’s manual, which is still in use. Her experience with the collection has been a lesson in perspective. “I learned so much sitting with a particular garment and puzzling through what it meant,” says Welsh. “I have found that in my professional life, sometimes the big picture tells you what you need to know—and sometimes it's the small picture, and you need to be able to flip your lens back and forth.”

Emma O’Neill-Dietel ’22 worked with the collection as a STRIDE scholar updating databases and learning how to take care of the garments. She credits Smith with encouraging her to experiment. “I started running our social media and putting pop-up exhibits in the campus center,” she says. “This really grew my interest in public history and in making history accessible, because both were free and super easy ways for people to get to know the collection.” O’Neill-Dietel, who is on the digital media team at PBS station WETA in Washington, DC, continues to run SCHCC’s Instagram. She echoes what countless other students and alums have said about the contribution that Smith and the SCHCC has made to women’s history. “Kiki has spent years toiling down there in the basement and nobody knowing that the collection is there. Nobody caring, nobody giving any funding,” says O’Neill-Dietel. “I would love for the collection to be able to spread its wings. And I would love for the collection to have more of a dedicated presence, both in-person and online for people to be able to access it more readily. Because the stories are all there. They just need to be heard.”

All photographs of the collection are by Anna-Marie Kellen for The Smith College Historic Clothing Collection.

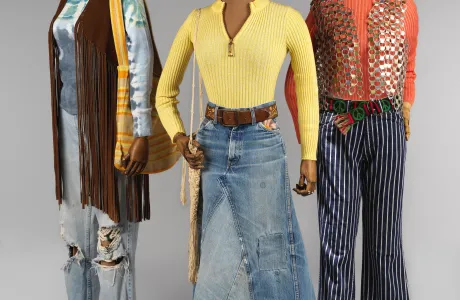

From the Collection